I decided to use a sketchbook to learn about and paint the plants I may choose to paint for the RHS in 2019. Firstly I researched wildflower plants which are under threat or declining as I wanted to relate them to my concern for our wildlife and the importance of reinstating meadowland. I discovered that some of the wildflower species were quite well known and many rare insect pollinators really depend on them.

Horseshoe vetch – Hippocrepis comosa

The first wildflower I began to study was Hippocrepis comosa (Horseshoe vetch). To my delight I found it growing in the meadow behind my house. Excitedly I looked it up in my Wildlife Key book only to find that there are many similar vetches and that this one was not Horseshoe vetch! I had found Lotus corniculatus (Bird’s-foot trefoil). The differences are quite obvious when you know what you’re looking at and it’s always wise to check your species carefully in a good wildflower book first.

‘The Wildflower Key’ was recommended to me as a good resource book. I also own the ‘Collins Wild Flower Guide’ which has lovely illustrations.

I went walking again in the meadow and discovered another vetch, again excited I checked it in my book but now I had found another vetch called Lotus tenuis (Narrow leaved Bird’s-foot trefoil – picture 4 below). I searched on holiday in Scotland, at other meadows in Bannerdown and Box Farm. Still I could not find Horseshoe vetch! Notice the beautiful red colour in the young flowers in picture 2. I will look again next year but have also planted some seeds in my garden and the back meadow in the hope that one will grow for me to paint.

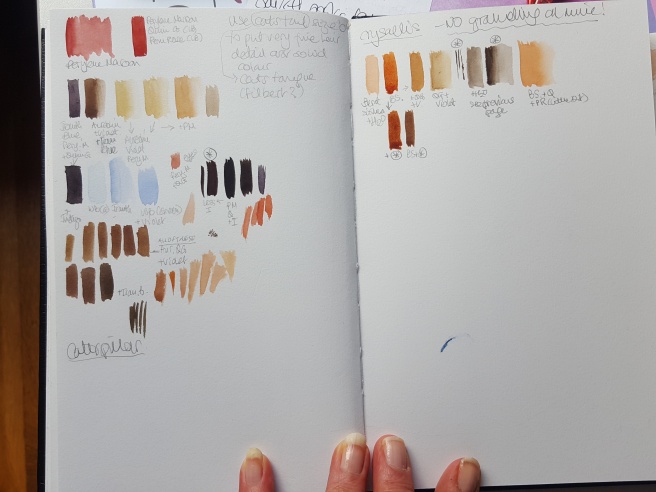

With a little more research and the help of existing botanical paintings, photographs online and my wildflower key book, I began to compose my page dedicated to Horseshoe vetch. I did not rely on photographs, as they can enhance colours incorrectly, to make my colour swatches but picked a piece of the two vetches I found in our meadow and took references from those. All 3 vetches have very similar colouring.

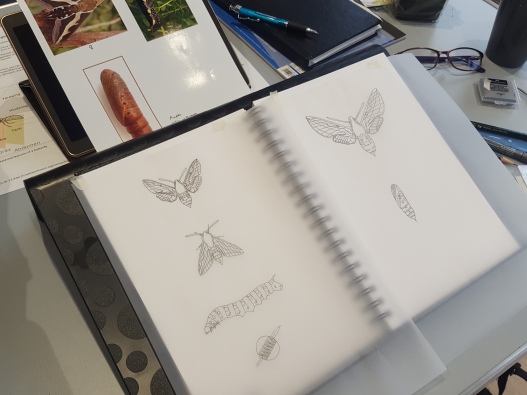

I included an Polyommatus bellargus (Adonis Blue) in my sketch as this butterfly is in major decline and Horseshoe vetch is an essential plant for both the Chalkhill and Adonis blue butterflies as their caterpillars feed solely on it. I used a set specimen I had bought and photo reference for positioning.

I studied the flower heads and seed pods too. My composition seemed like it was blowing in a summer breeze so I put a couple of meadow grasses in the background to add to this movement.

Now it was painting time! As you know I had taken my colour swatches from some suitable live subjects and so I began to mix up my colours . I placed them on the page together with a note of the colours I had used, this I will use for reference when the time comes to paint the final painting. The wings of an Adonis Blue have an iridescence to them and for this I laid a layer of Daniel Smith Iridescent Lilac over the blue part of the wing. You can just about see it in the photo below.

The final sketch included some pencil and black fine liner pen work as well as watercolour painting.

Where does the plants name come from? The name Horseshoe vetch is derived from the pea like flowers which are arranged is a horseshoe shape. The seed pods have also been described as resembling a horseshoe shape. In folk law it was said that if a horse trod on it, it would be unshod.

Ragged Robin – Lychnis flos-cuculi

The second plant I chose to study was Lychnis flos-cuculi (Ragged Robin). I chose this plant as it is declining in numbers and for the insect pollinator I chose a Bombus sylvarum (Shrill Carder Bee) which is also becoming rare. For this plant I studied a live specimen because luckily one had grown in my garden this year from seeds planted in the Spring. I was able to study it fully and dissect parts too. (*The photo of Bombus sylvarum was borrowed from Wikipedia as I did not have a specimen. They are slightly darker than this image and 10-15mm in size)

Mixing the pink was very tricky as it is a beautiful pale pink but bright as well. I tried a few mixes and found that Daniel Smith Opera Rose, W&N Permanent Rose and a little bit of Aureolin made the perfect pink. I then took more colour references and placed them onto my sketch page. The composition began to develop showing some of the inner flower detail, seed head and a close up of the hairy stem.

Later in the sketch I decided to study the flower’s internal structure more carefully and did a few diagram style illustrations to show this. This was my final sketch page.

Where does the plants name come from? Apparently this flower was used as a remedy for jaundice, stomach aches, toothache, headaches and muscular strains. The latin name ‘Lychnis’ comes for the greek work for ‘Lamp’. Flos-cuculi means ‘Cuckoo flower’. This is because it comes into flower when the cuckoo first starts to call. It has a rather straggly and messy in appearance but don’t get it wrong as it is the food plant of long tongued bees, butterflies love it and several species of moth.

Devil’s-bit Scabious – Succisa pratensis

The next wildflower I plan to study is a Succisa pratensis (Devil’s-bit Scabious) and there’s one in my garden just about to open! I’m really looking forward to studying this beautiful little plant.

Where does the plants name come from? The history behind this flowers name is quite interesting. “Scabious flowers were used to treat scabies, and other affictions of the skin including sores by the Bubonic Plague. The work ‘scabies’ comes from the Latin word ‘Scratch’ (scabere). The short black root was in folk tales bitten off by the devil, angry at the plant’s ability to cure these ailments.” Hence the name Devil’s-bit Scabious.

Yesterday our beautiful meadow was cut, so until next year I will have to await possible new species growing there, let’s cross our fingers!!

I hope you enjoyed this Blog and look forward to sharing my next one with you very soon!

*All photos, content, text and videos are subject to copyright – Jackie Isard Botanicals 2017